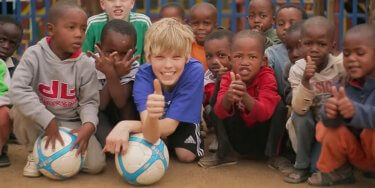

SHAPE America’s 50 Million Strong by 2029 commitment challenges each one of us to contribute to getting all of America’s children physically active, enthusiastic, and committed to making healthy lifestyle choices (SHAPE America, 2017). Of the approximately 50 million students presently attending America’s public schools, approximately 23 percent are estimated to be from immigrant and refugee backgrounds (Center for Immigration Studies, 2017). These young people face a myriad of challenges as they adapt to American culture. This includes navigating language, cultural barriers, stereotypes, along with negative attitudes regarding their residence and matriculation to the United States (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2017). With these students in mind, the following three considerations can help us meet our goal of improving the lives of all children regardless of race, gender, religion, or financial circumstances.

Get Educated

America, has a complex history regarding immigration and the treatment of immigrants. It’s a history that is politicized and routinely distorted (Culp, 2017). Data from the 2016 Current Population Survey (CPS) reported that immigrants and their U.S. born children number approximately 84.3 million people – nearly one-third percent of the overall U.S. population. Mexicans are the largest group of current immigrants in the country at 27%. Newer immigrants are largely represented from India (6%), China and the Philippines (5% each), El Salvador, Vietnam and Cuba (3% each), and the Dominican Republic, Korea, and Guatemala (2% each). Immigrants from these ten countries constitute roughly 60% of the U.S. immigration population. Other places of origin for immigrants in smaller percentages include Ireland (Northern Europe), France (Western Europe), Greece and Spain (Southern Europe), as well as Romania, Russia, Ukraine, and Bosnia (Eastern Europe).

Immigrants and refugees are often inaccurately perceived to be members of the same group. Generally, an immigrant is a non-native person who chooses permanent residence in a foreign country and has obtained the legal right to seek citizenship and take up employment. In contrast, a refugee is an individual who has been forced to flee his or her home country because of threat of war or persecution (United States Department of Homeland Security, 2017). Other designations include undocumented immigrants (who do not seek legal status for residency), asylees (people who meet the definition of a refugee and are already present in the United States not looking to return to their home country), and individuals who have been forcibly displaced (for reasons including population transfer, natural disaster, ethnic cleansing, deportation).