PHE America Repeats

10 previously published articles in 10 days that we think you will enjoy

Reprint 3 of 10

(Originally published – January 3, 2018)

Dear Quitting Self:

PHE America Repeats

10 previously published articles in 10 days that we think you will enjoy

Reprint 3 of 10

(Originally published – January 3, 2018)

Dear Quitting Self:

Dear Quitting Self:

Excuse my blatant disregard for pleasantries, but let’s clear something up right away. The only reason you – my quitting self – even exist is because I love not only what I do, but the profession that allows me to do it. My passion for the profession and the kids I teach created the space in which you live.

I’ve learned that when you love something, when you have an intense emotional investment in something, when you truly care, there will always be ups and downs, great days and not-so-great days, moments of extreme joy and moments of pure frustration. The downs, the not-so-great days, and the frustrations are times that wake you up like the loudest, most annoying alarm clock ever invented. They make me question what I’m doing and whether it’s worth it. They create doubts. And although these doubts will probably always exist, I’m ok with that. When I started my teaching career I knew it would be hard, really hard. What I did not know was some of the places those difficulties would grow from.

Don’t Just be a Future Professional, Be the Future of the Profession

-A letter to future professionals-

To whom it may concern

When will “New PE” simply become PE? That’s a question I think about from time to time. It speaks not only to the direction of the profession, but also the stereotypical lens that outsiders view us through. It’s a question that pops in and out of my head, typically without too much consideration, and usually in a moment of reflection, or frustration. At last summer’s National PE Institute in North Carolina, presenter Naomi Hartl mentioned how she and Sarah Gietschier-Hartman had been discussing this same question. And Naomi had an answer.

The story of Welles Crowther is not only a heroic one, but an educational one as well. It displays many of the ideals that we try to instill in our students on a daily basis such as leadership, confidence, critical thinking, social responsibility, selflessness and persistence to name a few.

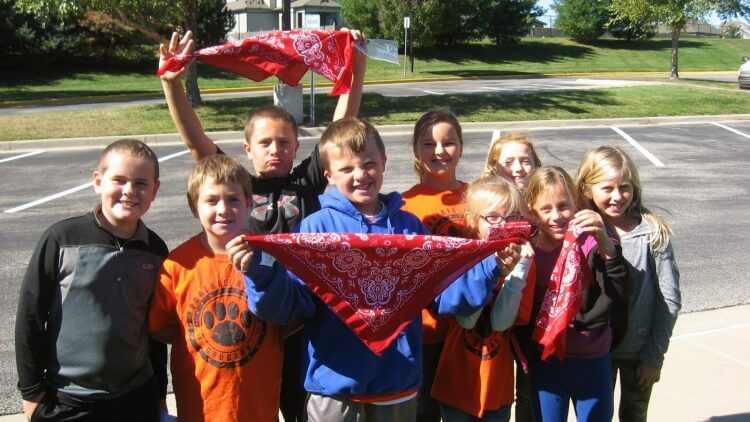

Welles Crowther grew up in Nyack New York, where he is remembered as a star athlete, community leader and the boy – soon-to-become man – with the red bandana. When Welles was a young boy, his father gave him two bandanas and some fatherly advice. His dad told him that one of the bandanas was for show and the other one was to blow his nose with. One of those bandanas was red and Welles had it with him everywhere he went. Whether it was in his pocket or under his lacrosse helmet he was never without his red bandana.

Upon graduating from high school Welles went on to play lacrosse at Boston College, and from there he went to work in the World Trade Center. Welles was at work on September 11th. He was in the buildings when they were hit and he remained in them when they fell. However, unlike many people trapped in the buildings that morning, Welles had an opportunity to get out. Instead, he chose to help others to safety.

Most teachers I know are always looking for ways to improve their practice so they can better serve their students. We strive to develop more effective assessments, more engaging lessons, better classroom management techniques, stronger interpersonal relationships, the list goes on endlessly.

When I reflect on my own teaching and try to answer the question “How can I better serve my students?” I find myself challenged with a related question, “Where should I strive to have most impact?” Should it be in the gym and on the fields, or on the streets and in the yards?

I have always been a firm believer that a strong physical education program (among many things) serves as the foundation for a healthy life, but wonder whether my teaching reflects this. It is easy to say that PE can provide the foundation for healthy living, it is even cliché to a degree, but I still wonder, “Am I truly teaching all of my students how to do it?”

In the world of physical education, there are times when the internalization of teaching models, concepts and strategies is, in my opinion, rushed or incomplete. Models that are not specifically designed for physical education are often either glossed over due to the perception that “we are different” and they do not fit in our discipline, or they are quickly dismissed. For example, what I hear in regard to performance-based assessments from other PE professionals is something to the effect of, “Yeah, we do that every day. Our students perform a skill and we assess it.”

Although the verbiage matches (performance and assessment), if you stop there the opportunity for tremendous student growth is lost. Performance-based assessments (PBA) are much more than performing a skill. They provide students choices in an area of study, while allowing opportunities for them to both explore an essential question and share what they have learned. There are four main components to a PBA: