With the rise in obesity and sedentary rates, and subsequent chronic conditions, it seems imperative, now, perhaps more than ever before, that we encourage children and adolescents to be physically active. But, what if a lack of interest stems from fear of injury?

While ACL injuries disproportionately affect female athletes, accounting for 69% of serious knee injuries when compared to their male counterparts (Gomez, DeLee, & Farney, 1996), the latter is certainly not excluded from this injury pathology. As practitioners, our role is not limited to performance improvement, we must also be able to identify, provide, and prevent potential injuries. Running faster and jumping higher should no longer be the hub of engagement in physical activity. Alternatively, in order to cultivate lifelong movers, we should be training proper movement strategies. Thus, reducing the risk of injury, the associated fear, and consequently increasing the longevity of a physically active lifestyle.

This article was originally published on January 3, 2020.

Identify Faulty Movement Strategies

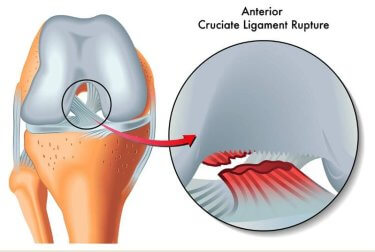

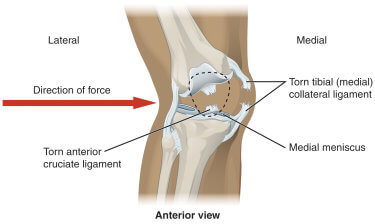

The first step in preventing anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries is to identify faulty movement strategies. There are four common faulty movement strategies that unconditioned/untrained adult and adolescent males and females typically exhibit in jumping and landing during sport and recreation play: 1) quadriceps dominance 2) ligament dominance 3) leg dominance and, 4) trunk dominance. Quadriceps dominance is characterized by a stiff-legged landing and/or the knees traveling beyond the toes upon impact, resulting in the center of gravity moving beyond the base of support. Ligament dominance is characterized by an inward knee movement or collapse (i.e. valgus) and/or a trunk tilt to one side or another. Leg dominance is characterized by preferential use of one leg over another. Lastly, trunk dominance is characterized by the movement of the trunk beyond the toes and/or movement of the trunk to one side or another.

It is important to remember that the human body is a kinetic chain; everything is connected. A faulty movement strategy utilized lower in the chain may then affect movement higher up the chain (e.g., leg dominant landing with trunk movement to one side). In addition, during a quadriceps dominant movement (e.g. leg extension), recruitment and contribution of the quadriceps outweigh that of the antagonist hamstrings. This may occur due to a lack of strength in the posterior chain (i.e. muscles on the backside of the body), including the gluteal and hamstring muscle groups.

The second faulty movement strategy, ligament dominance, wherein the knees collapse inward, is often propagated by a muscle imbalance between two of the muscles within the quadriceps ensemble. If the medial (inside) quadricep is underdeveloped (i.e. lacking strength), its role in contracting to prevent inward knee collapse will be lessened. Moreover, females may be at a higher risk to move in this way due to a larger Q-angle. The Q-angle is the angle formed by a line drawn from the hip bone to the center of the patella. Because the female body tends to have wider set hips, this larger angle is a predisposition for the presence of a ligament dominance.

At times, leg dominance, the third faulty movement strategy, can be the most difficult to identify. Quick observation might lead us to believe the legs are symmetrical, simply based on their appearances. However, even small discrepancies in the muscle activation and function of these limbs would suggest the presence of leg dominance. Even as children, we rely on one leg more than the other for a variety of tasks, leading to an imbalance that can be perpetuated throughout the lifespan. Ideally, the forces associated with movement tasks would be evenly distributed between the right and left legs. When a leg dominance is present, the dominant leg will assume the bulk of the necessary involvement (i.e. contribution and attenuation) for a given movement task, thus exposing it to large forces meant to be equally disseminated.

Lastly, the fourth faulty movement strategy, trunk dominance, is often linked to a quadriceps dominance. In an effort to govern the accompanying forces of a movement task, students and athletes may shift their center of mass forward, therefore relying on their quadriceps. Additionally, the abdominals must provide assistance in maintaining a neutral spine. Thus, a deficiency in the abdominal contribution can also perpetuate a trunk dominance.

Provide Instructional Cues to Correct Faulty Movement Strategies

Once the educator identifies potential faulty movement strategies, they can provide appropriate instructional cues and appropriate training practices. When working with a student that is quadricep dominant, encourage them with verbal cues by stating, “push the hips back; sit back upon landing,” and “engage the posterior muscles” (gluteus maximus and hamstrings). These verbal cues will help the student focus on their movement and in this case, will nurture a softer landing, inspired by a bend in the knees.

In the case of ligament dominance, where the knees collapse inward during loading or landing, an appropriate instructional cue during a movement task (e.g., ascent or descent in squatting, landing from or loading for a jump) would be “knees in line with toes.” While there aren’t a lot of cues that truly speak to the source of this occurrence, making them aware of this faulty movement strategy has proven to be one of the most influential means of correcting it. Once a student learns to ascend, descend, land, or load while keeping their knees in line with their toes, the ACL will undergo less strain throughout all phases of these movement tasks.

When you identify a leg dominance in a student or athlete, the appropriate instructional cue to use really depends on the task at hand. For instance, when leg dominance appears during a landing task, it is important to encourage the student or athlete to “land with both feet at the same time.” However, if the task is a back squat, using a cue such as, “distribute the weight evenly between the right and left legs,” is more appropriate.

Since trunk dominance is one of the most apparent faulty movement strategies. Simple and to the point instructional cues include, “push the hips down,” “neutral spine,” and “proud shoulders.” Remedying this dominance will not only help to reduce the occurrence of quadriceps dominance but will also reduce the strain experienced by the lower back. In a sport setting, an athlete utilizing a trunk dominant strategy unintentionally moves their center of mass over and often beyond their toes. Thus, if another athlete were to bump into him/her from behind, they would most certainly lose their balance and tumble to the ground.

Implementing a Training Plan

Identifying faulty movement strategies affords the practitioner an opportunity to provide students and athletes with instructional cues to stimulate safe and effective movement strategies to prevent the risk of an ACL injury. Moreover, educators may want to consider providing students with a plyometric training program designed to increase hamstring muscle recruitment and activation. Greater contribution from the hamstrings will subsequently reduce the strain placed on the ACL. An example of a practical plyometric training program designed for post-pubescent adolescent females is provided (Table 1). This program can be modified to fit the needs of the students and athletes you teach. For example, if you are teaching strength development for youth males, increase the number of foot contacts. On the other hand, an educator working with elementary age youth would decrease the number of foot contacts and reduce the high-intensity exercises. Allotting fifteen minutes a day, three days a week to identify, provide and prevent the risk of ACL injury can alleviate a myriad of uncertainties, including fear of injury. By taking time as educators to identify fault movement strategies and provide corresponding instructional cues, we can continue to strive to meet our responsibility to develop lifelong movers.

Table 1: Practical Plyometric Training Program

| Training Week |

Training Volume (Foot Contacts) |

Plyometric Drill |

Sets X Reps |

Training Intensity |

|

Week 1 |

90 |

Single-Leg deadlift Jump & Reach Lateral Hop-to-Balance Power Skip |

2 X 10 2 X 10 1 X 15 (each) 1 X 10 (each) |

Low Low Low Medium

|

|

Week 2 |

140 |

Single-Leg Deadlift Jump & Reach Lateral Hop-to-Balance Jump to Box Power Skip

|

2 X 10 2 X 10 (each) 2 X 10 (each) 1 X 10 (each) 1 X 10 (each) |

Low Low Low Low Medium |

|

Week 3 |

120 |

Squat Jump Single-Leg Squat Jump to Box Lateral Box Jump Jump from Box Power Skip

|

2 X 10 1 X 10 (each) 2 X 10 1 X 10 (each) 2 X 10 2 X 10 |

Low Medium Low Medium Medium Medium |

|

Week 4 |

134 |

Jump & Reach Single-Leg Deadlift Split Squat Jump Lateral Box Jump Single-Leg Hop Depth-Jump

|

3 X 10 2 X 10 2 X 6 (each) 2 X 6 (each) 2 X 6 (each) 2 X 6 |

Low Medium Medium Medium High High |

|

Week 5 |

136 |

Jump to Box – SL Jump from Box Double-Arm Bound Single-Leg Hop Depth Jumps Depth Jump to 2nd Box

|

2 X 10 3 X 10 2 X 8 (each) 2 X 6 (each) 3 X 5 3 X 5 |

High Medium Medium High High High |

|

Week 6 |

132 |

Jump to Box – SL Jump from Box Single-Leg Hop Depth Jumps Depth Jump to 2nd Box Depth Jump w/ LJ |

3 X 10 3 X 10 2 X 8 (each) 3 X 5 3 X 5 2 X 5

|

High Medium High High High High |

References

Gomez, E., DeLee, J., & Farney, W. (1996). Incidence of injury in Texas high school girls’ basketball. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 24, 684-687.